Dark Fiber

2014-15, 2016, 2019

Marissa Lee Benedict and David Rueter

___

“DRAW. In A Thousand Plateaus, to draw is an act of creation. What is drawn (the Body without Organs, the plane

of consistency, a line of flflight) does not preexist the act of drawing. The French word tracer captures this better: It

has all the graphic connotations of “to draw” in English, but can also mean to blaze a trail or open a road. “To trace”

(decalquer), on the other hand, is to copy something from a model.”

– Brian Massumi, “Notes on the Translation and Acknowledgements,” A Thousand Plateaus:

Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari

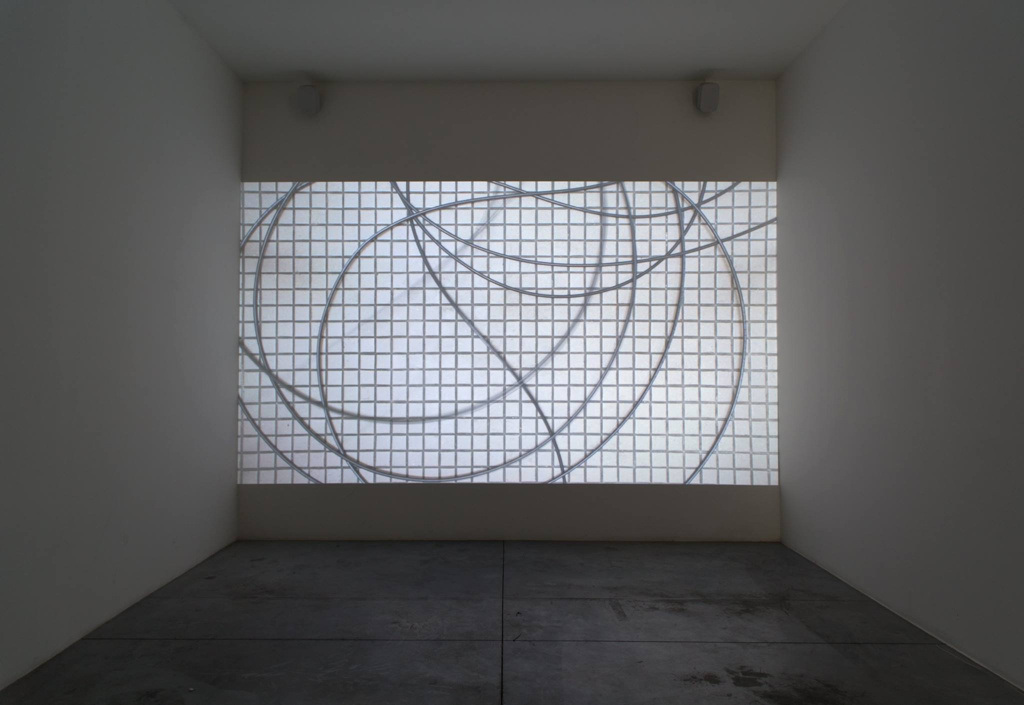

Viewers entering the video installation, Dark Fiber (2015-19), are greeted with scenes of Benedict and Rueter digging, burying, pulling, and cutting a fifiber-optic cable in the shadows of large-scale infrastructure. Locations such as the US/ Mexico border wall, Chicago-area refineries, and an Antwerp shipping canal segue into urban, then interior spaces, gradually reducing in scale and increasing in strangeness, until a tiny specialized machine cuts a single strand of fifiber. The exhibition site eventually appears on camera, inviting viewers to literally and uncannily connect the fifilmic industrial worlds with the installation space. The video, which inaugurated the artists’ collaboration in 2014, has traveled to six exhibitions around the world.

At the time of the work’s conception (2014) a quick Google image search for the phrase “internet infrastructure” revealed little about the sites, materials, and labor of internet infrastructure. Searches instead retrieved a procession of tangled, blue-tinted node-link diagrams. The results for “cloud computing” were (and still are) even more optically jejune; one could reasonably think that the internet is simply carried along by a combination of blue icons, arrows, and boring magic.

In telecommunications industry jargon “dark fiber” is a term for unused, or “unlit” fiber optic cable. As of 2014, adding a few latent strands to a fiber rollout cost little compared to leasing land, negotiating rights-of-way, digging trenches, and sawing through city streets. Telecom companies frequently opted to overbuild capacity in anticipation of future demand. The demand for this capacity became, in many instances, superfluous with technologic leaps that paced increasing amounts of information into light wave frequencies. The latent, now surplus, cable became a real estate opportunity for a growing number of private companies to lease this unused fifiber to create their own exclusive networks.

The node-link diagram, a mathematical abstraction that is now shorthand for the complexity of networked society, can obscure more than it reveals. Frame-by-frame, Dark Fiber draws a different approach to network representation, suggesting that one might instead follow a single line: one that hops between systems and scales, through vast landscapes, industrial infrastructure, media apparatuses, walls and conduits, lived space, and imagined worlds. Histories of property, white settlement, fronterism, innovation, and technologies of "progress," trace, and are traced by, this line. The result is not an understanding delivered whole, but a subjective experience, one afffforded by walking a path.

___

Dark Fiber was exhibited first at the ︎︎︎Chicago Artists Coalition (US) as a solo exhibition in 2015. The video is site adapted (the ending reshot) for each exhibition of the work.

Consequent sited-adapted exhibitions of the video installation took place at: EXPO Chicago (US) in 2015 (selected by Jacob Proctor, formerly of the Neubauer Collegium at the University of Chicago); ︎︎︎The Works: Artists In and From Chicago in 2015, curated by Abigail Winograd and Dieter Roelstrate for Contemporary Art Brussels (BE); ︎︎︎Placelesness in 2016, curated by Jason Judd for the Illinois State University Gallery (Normal, IL, US); ︎︎︎Dimensions of Citizenship: Architecture and Belonging from the Body to the Cosmos for the U.S. Pavilion's "Transit Screening Lounge," curated in part by Iker Gill, for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale (IT); and Dimensions of Citizenship for Wrightwood 659 (Chicago, US).

Special thanks over the years to: Meghan Moe Beitiks, Alex Benedict, Ingrid Burrington & Creative Time Reports, Lindsey french, CLUI & Matt Coolidge, Pat Elifritz, Jeremiah Jones, Brian Lee, John & Patricia Lee, Adam Mansour, Juan Luis Olvera, Marc & Anne Rueter, Eleonore de Sadeleer, Teresa Silva, and Andy Tokarski.